This is the text of the speech I delivered at the annual Remembrance Sunday service at the War Memorial in Scotter, Lincolnshire:

“Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.”

These remarkable words from St John’s Gospel are appropriate to recall when we remember the unprecedented sacrifices of those who fought and died in the appalling horror of the First World War.

We are here today to honour and to remember that sacrifice, irrespective of class, creed, or colour.

The sacrifice of those who died in the Great War is all the more remarkable for how instinctive it was.

When the call of King and Country went out, hundreds of thousands answered it immediately. Some even lied about their birthdays in order to make the minimum age for enlistment.

And out of that instinctive action flowed instinctive bravery.

In this country and across much of the Commonwealth, our highest award for bravery in the face of the enemy is the Victoria Cross.

Thirty miles from where we sit today, Sergeant William Henry Johnson of 1st/5th Battalion, Sherwood Foresters was born.

On 3 October 1918, Sgt Johnson charged a German machine gun platform single-handedly, bayonetting a number of the occupants and capturing two machine guns. Wounded in that effort, he carried on regardless, charging another machine gun and putting it out of action with a grenade.

Sgt Johnson’s instinctive valour on that day earned him the Victoria Cross.

On the same day, one of his comrades from the 1st/5th Sherwood Foresters, Herbert Eminson, was killed.

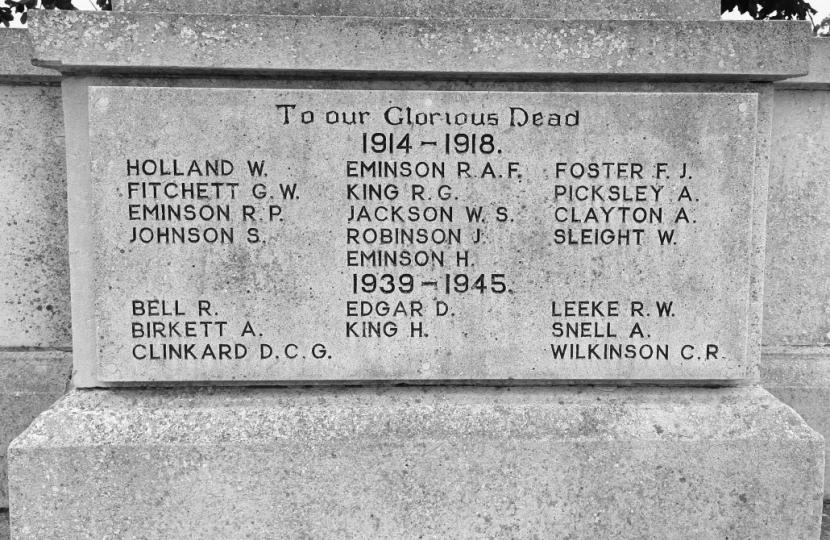

Eminson was 37 years old at his death, and came from right here in Scotter where his name and those of other Eminsons can be read on the war memorial.

One of his cousins, Robert Astley Franklin Eminson, was an officer attached to the 2nd Brigade of the Machine Gun Corps, and his men were at the Somme next to those of the 1st Northamptonshire Regiment.

One of the sergeants of the 1st Northants, Jim Henson, wrote to the mother of his comrade Sergeant Samuel Yerrell:

“Poor Sam has been killed this morning. I have been up to his company and found out all about it. Tonight I am going to see him buried respectably. First off he had both arms shattered by a bomb, and as a fellow was bringing him towards our trench they fell exhausted. Then a Second Lieutenant jumped out of our trench and went to help them. As soon as he got to Sam a German fired at them, the bullet passing through Sam's back and right through the officer's heart. The officer was killed instantly, and poor Sam died an hour later before I could get to him. He died a soldier's death. The brave officer who got killed trying to save Sammy was Lieutenant Eminson.”

Lt Robert Eminson, just 24, was buried at the Becourt Military Cemetery, but many of his comrades who fell at the Somme had no known resting place.

Over 72,000 of their names are recorded on the walls of the monumental Thiepval Memorial to the Missing.

The names of three men from Scotter can be found there: George William Fitchett, Sidney Johnson, and George Rowland King, known as Roland.

King’s parents, Walter and Demaris King, ran the fish-and-chip shop on the Gainsborough Road from 1910 to 1940.

Roland enlisted at Grimsby in May 1915, just 17 years old, and arrived in France in October of that year.

On July 1st 1916 – the first day of the Battle of the Somme – Private King was in the first wave over the top at 7.30 in the morning.

With his comrades in the 2nd Battalion, Lincolnshire Regiment, and in the face of concentrated machine gun and rifle fire, Private King managed to advance two hundred yards into the German lines.

On that day alone, the 2nd Lincolns had casualties of 21 out of their 30 officers, and 450 of their 700 men.

Roland, as he was known, fought on, despite being wounded later in the month as the battle continued.

On the morning of 10 November, as his unit were relieving Sherwood Foresters near Lesbeoufs, the 2nd Lincolns came under heavy shellfire, and Roland was killed.

His commanding officer, Capt. G. Thatcher, wrote to the King family, saying:

“We all feel his loss very much, as he was a good soldier, always carrying out his duties with the greatest steadiness and courage. He joined the 2nd Lincolns on May 20th 1915 and was only 17 years of age. He was wounded in the neck and chest in June 1916 and after between seven and eight weeks in hospital returned to his duties in the trenches in France.”

The Lincolnshire Chronicle wrote that “The sympathy of the whole village folk is felt with the father, mother, and family in their sad bereavement.”

Just a week after Roland King’s death, and months after it commenced, the Battle of the Somme ended in an inconclusive stalemate.

These are less than a handful of histories, and from just one village, and just one battle.

But stories like theirs are repeated on the war memorials of a thousand villages, towns, boroughs, and cities up and down Britain, and of course in other countries too.

What lesson can we learn from their sacrifice other than that which the Evangelist reminds us: Their love was proven by their sacrifice, and the point of their sacrifice was love. We must forget neither their love nor their sacrifice.

For “Greater love hath no man than this: that a man lay down his life for his friends.”